It is a good idea to formulate boundaries and requirements for the desired literature before you begin your systematic literature search. This helps to make your search more precise and the literature selection more objective.

Inclusion criteria can be used in several ways. They can, for example, be included as keywords, as a filter using the database's limitation options, or as a criterion when you manually review the search results.

Many databases allow you to roughly sort the search results through various limitations in the database. This can include:

- Publication year – do you only want research from the last 5-10 years?

- Source type – do you want research articles but not books, reports, or conference contributions?

- Population – gender, age, or grade level?

- Geographical limitation – only Danish or Scandinavian conditions?

- Peer review – should the results be peer reviewed or not?

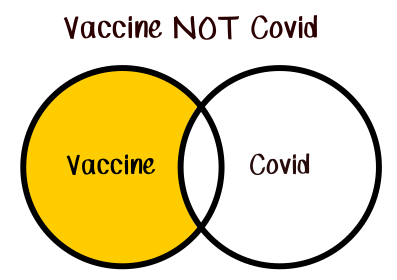

Be careful with excluding using the operator NOT. For example, excluding the word "boys" can easily result in missing literature where girls are compared with boys, or where both genders are included. In such cases, it may be necessary to select the literature by screening a larger search result based on title and abstract. It takes time but also ensures that you do not miss relevant research.

Especially in your selection of literature, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria ensure that you remain objective in your selection or rejection. The selection is based on predefined criteria of relevance to the topic – not on a spontaneous assessment of support for your method or viewpoint.

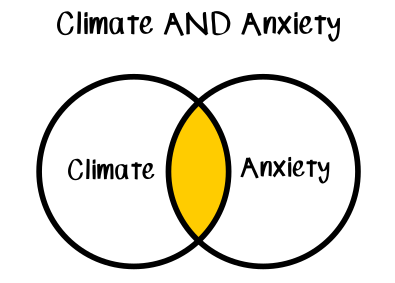

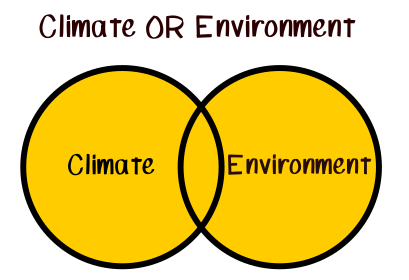

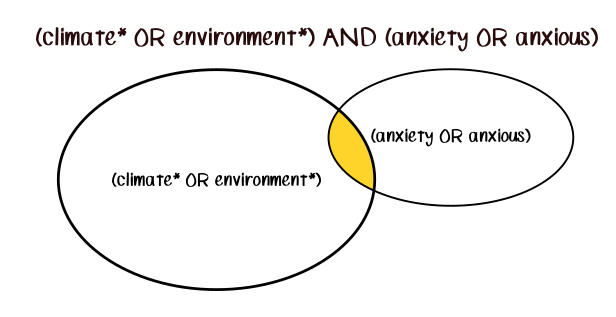

![[Translate to English:] Eksempel på en sammensat søgning i en database - med brug af booleske operatorer, som beskrevet i teksten ovenfor.](/fileadmin/_processed_/3/5/csm_Systematisk_litteratursoegning_Booleske_operatorer_databaseeksempel_sammensat_c9adfdaefa.png)